Our First Find

December 10, 2023

This is the story of an end to a journey that started in 2007!

Way back then, my friend Jon and I learned that weather balloons are launched twice a day from the sleepy Quillayute airport, in the very northwest corner of the continental United States, about 100 miles west of our homes in Seattle. One sunny afternoon, we flew out there to see a launch. At the edge of tarmac with weeds growing through every crack, we found a squat building belonging to the National Weather Service. It was one of the few structures on the largely empty airfield. Inside, behind a grey metal desk covered with papers, sat a pleasant older lady surrounded by racks of decades-old radio and computer gear. She told us that we’d just missed the launch but was happy to show us all the receiving equipment.

We learned that radiosondes—the technical term for the devices that sense the weather—are launched simultaneously from over a thousand sites around the world every day. Each is hoisted 100,000 feet or more into the stratosphere underneath a large hydrogen-filled balloon, transmitting temperature and pressure data during its journey. When the balloon pops, the sonde falls gently back to Earth, landing dozens or hundreds of miles downwind from where it started.

“If you ever find one of these out there, do me a favor and throw it away,” she told us. About ten percent of the balloons she launches are found and mailed back using the return address label on the package. “When I get one back I have to reuse it, but the old ones never work right.”

I finally returned to Quillayute a couple of years ago, only to discover that the lady was gone forever, replaced by an auto-launching robot. We’d lost our opportunity to see a sonde before it was launched, so the only option now was to find one after it landed!

In the years since that first trip, finding radiosondes has become a popular hobby, particularly in Europe. Sonde-hunters worldwide collaborate to track sondes and try to retrieve them. The sondes’ radio transmissions are not encrypted and include their GPS-derived latitude, longitude and altitude. Hobbyists have learned to receive and decode the data, and have set up hundreds of listening posts worldwide that all feed into a volunteer-run website called SondeHub. In 2022, I set up a receiver in a west-facing window of my condo.

Unfortunately, we soon learned that finding sondes isn’t so easy in the Pacific Northwest. Launches from Quillayute almost always end up somewhere inaccessible, like the ocean or deep in the old-growth Olympic rainforest. Instead, I spent a year writing software to help with the search—analyzing typical landing sites by drawing heatmaps and seasonal landing calendars, and creating an automatic notifier that would email us when it detected a sonde that landed somewhere that might be retrievable.

Our preparation finally paid off this past Sunday morning. I woke up to an email from my notifier with the subject line of “GROUND RECEPTION!”—indicating a rare situation where the sonde had maintained good enough radio contact that it could be tracked all the way to the ground. Knowing the precise location makes the sonde far easier to find, even in dense vegetation where visibility and mobility are limited. Soon after the email, I had a message from Jon asking if we should go for it. The sonde had landed in a forest about 1,500 feet from a road with a convenient parking area nearby. Forest landings usually end up at the top of a 100-foot-high tree, but the tracking data showed this sonde was at roughly the same altitude as the terrain. Even more crucially, Jon looked up the photos on Google Maps’ aerial view and noticed this landing was on the edge of a region that looked like it had been logged in the last couple of decades: the trees were much sparser and shorter than adjacent areas. He also looked up the plats to discover the parcel was public land, owned by the Washington State DNR. We decided to hike for it! Unfortunately, we forgot to look at the topo map before making this decision.

We got our gear together and took the ferry from Edmonds to Kingston, then drove a half-hour to the parking site we’d seen on the map. The sonde was nearly due west. The first challenge was to cross a stream. We walked down its east bank for a few hundred yards until we found a spot that looked suitable and carefully made our way to the other side, hopping from rock to rock as the water rushed past. Then came the slow hike upwards: though the sonde was only about 1,500 feet away laterally, it was also 1,000’ higher than the road! There were no trails. We carefully picked our way upwards through the steep woods, occasionally backtracking when we’d come across a sheer face or ravine. The ground was a dense tangle of broken branches, thorny shrubbery and wet leaves that was often knee-deep. We had to raise our feet high and mind each step as sinking into the old growth was a constant threat. We both fell a few times. The climb was not easy!

After nearly 90 minutes of fighting our way uphill, we reached the more recently logged area and could move around a little more easily. Our phones’ GPS led us to the sonde’s coordinates. But after ten minutes of searching, there was no sign of it. The sonde’s coordinates and our own both had some error, and the trees were still dense enough that we couldn’t see very far.

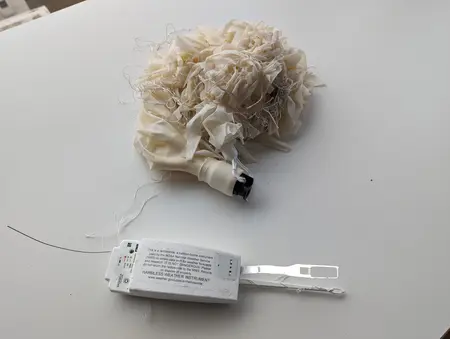

Daylight was beginning to fade and our turnaround time was quickly approaching. Jon then had a good insight: my receive site had been in contact with the sonde for 8 hours while it was on the ground, and had received thousands of GPS points while it was stationary. Instead of looking at the last GPS point, as we had been, we should instead look at the entire point cloud and head to the center of it. Not more than a minute later, we spotted a tree with string in it! Our eyes followed the string and, sure enough, hanging from a low branch about 2 feet off the ground, our long-sought quarry awaited us!!

The string was still all in one piece, going from the sonde at our feet up to an adjacent tree 30 feet high. The balloon was not visible. We started yanking on it and the shredded latex balloon finally came into view high above us; a few more pulls and it came down. I stuffed the whole thing into my jacket pocket and we headed back downhill, crossing the stream again and reaching the car 15 minutes before sunset. We ate well-deserved burgers at a diner just up the road and congratulated ourselves on having finally finished a chapter we’d started 15 years ago.